Now is the time to start propagating your grape vines by cuttings. I am reposting the article that Steve Casscles and I collaborated on earlier this year. Good luck and Happy New Year!

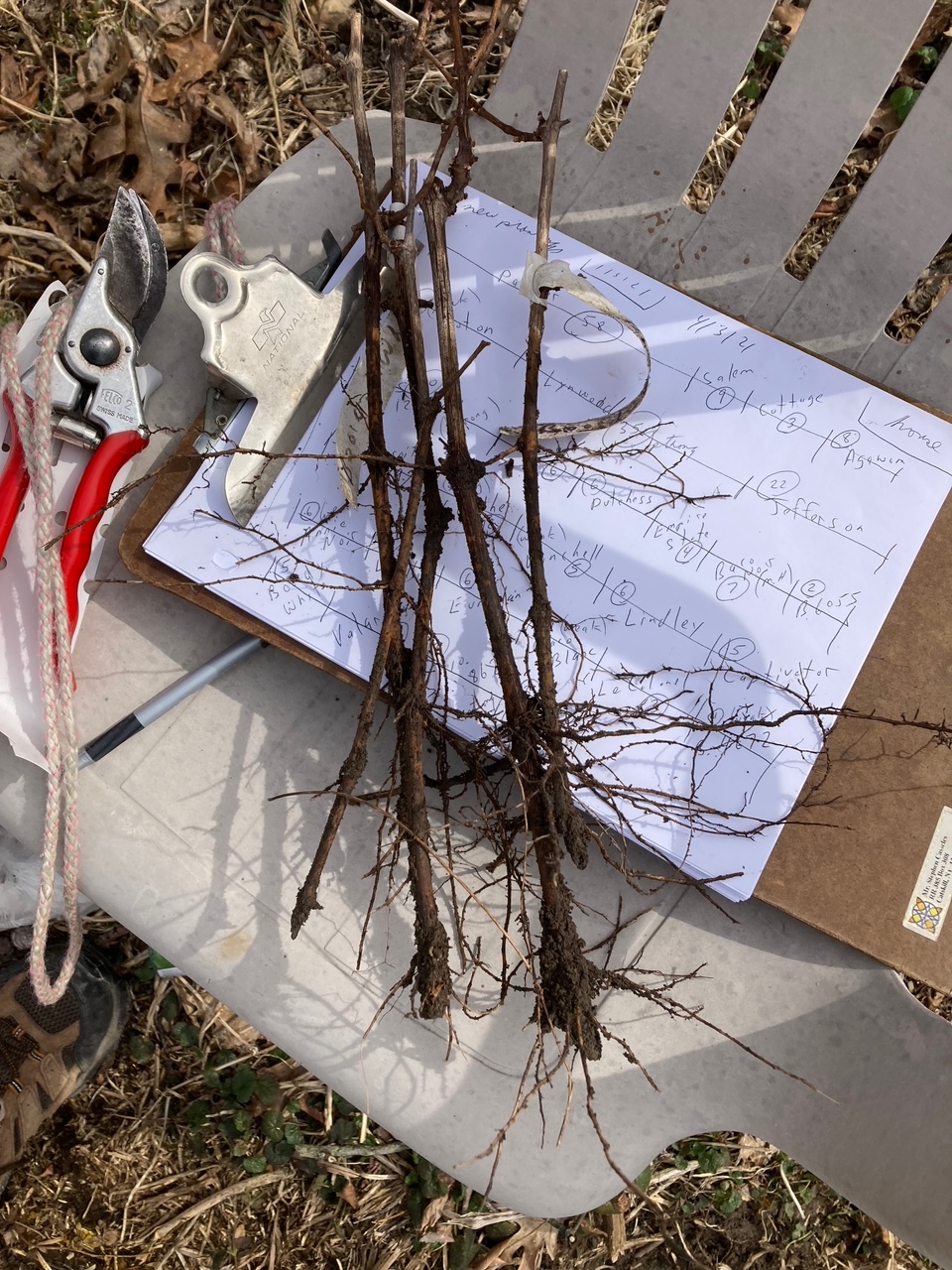

The following article is a collaborative effort between myself and Stephen Casscles, a leading authority on the propagation and cultivation of cool climate and heritage grapevines. It is a detailed account of the procedures for propagating new grapevines from the cuttings of an existing vine. Thank you Steve for being so generous with your time and knowledge. All photos in this article are courtesy of Stephen Casscles. If you need more information about how to propagate vines, consult older books written by Philip Wagner, which are still available, or contact your local cooperative extension agent who can direct you to excellent brochures that have been produced by your local agricultural state university.

If you have or can obtain clippings from a grapevine that produces excellent fruit, it is easy to reproduce as many vines/clones of that vine as you want. Starting new vines from the clippings of a mother vine ensures you will grow an exact copy of the vine and it will crop the same quality grapes as the original vine. Be sure that the mother vine that you select for your cuttings is strong, and exhibits no indications of viruses or diseases. Some vines, that have curled leaves, odd-looking clusters, or off-leaf colors have been contaminated with a virus. Do not use these vines as you are simply propagating diseased and virus-laden vines and not the strong virus-free vines that you want.

The next step is up to the propagator, but Steve said he was taught to nip off a straight cut one inch above the top bud and make an angled cut at the bottom of the cane just below the bud node. Making your angled cut at the bottom of the stem easily shows where the top of the cutting is from the bottom which makes it easier when setting out your nursery cuttings, it also allows the cutting to be easily planted in the soil. No matter how you cut your ends, make sure you are consistent so that you will always plant your cuttings correctly, bottom side down in the soil. Dipping the bottom end of the stem into rooting hormones helps promote root growth, but is not necessary. You can find rooting hormones at your local garden center or nursery. If you are only rooting a few cuttings, fill a potting container with your local soil, if it is good well-drained loam soil, if it isn’t mix it with potting soil to improve its drainage. Make sure your container is deep enough to accommodate your clippings, but if you are propagating a lot of material consider digging a shallow trench and reserving enough loose soil to fill in around your stems.

These trenches can easily be located in your vegetable garden, since this soil has been worked up for many years, and often has a fence around it to keep out the wildlife that may like to browse on your newly installed cuttings. When planting your cuttings, bury them vertically three to four nodes deep with the bottom side down into the ground, leaving the remaining nodes exposed above the soil level. Remember to plant the bottom of the stem down with the straight-cut end above the ground.

Keep the soil well watered, but not soggy throughout the first year when your cuttings are establishing themselves. For those in potted containers, the cuttings should be placed in a frost-free location with bright indirect sunlight. If you have more than one row of nursery cuttings in your nursery, it is recommended to mulch the cuttings with straw (not hay) to keep down the weeds and retain soil moisture.

Steve explained the difference between taking cuttings from your vine and propagating them as a single project and cloning in which you separate individual canes that have a certain desirable mutation to create an entirely new variety of the original grapevine. Steve gave me an excellent example that was easy to understand. “My understanding is that cloning would be finding an abnormal sport of a vine that is different and you cut that unique cane off to propagate it. For example, Frontenac Gris is only a regular Frontenac when it was noticed that a separate cane had bronze-colored grapes and not red. So cloning would be separating and propagating that “clone”, but if you are propagating wood, you just collect your wood and go at it.”

You must plant more cuttings than you need to compensate for some not surviving. As a dear departed friend of Steve’s, Joel Fry of the Bartrams Garden in Philadelphia used to say, “Plant two of everything, and one will die”. How many to plant is the question. Steve offered his advice based on years of experience in this area of viticulture. “I find that different varieties propagate at different rates. For example, Baco Noir, which is a part Riparia variety tends to have a higher success rate because it is a Riparia. Even with Riparia, I would plan for a 20% non-success rate for varieties such as Delaware, which is a part Bourquinian species hybrid, do not take as readily, so I would expect a 40% death rate.” I would recommend propagating as many cuttings as possible using only the strongest ones to satisfy your needs and giving the extras away. Vines can also be rooted in water, but you will need to change the water regularly to prevent disease. Once you see the stems/cuttings rooting, you must transplant them into the soil.

Whether you set out a nursery in your home garden or place them in pots in the spring, you need to wait an entire year to ensure that your cuttings have sufficient roots before they are set out in the field the following spring. After your cuttings have developed a strong root system they can be transplanted to their permanent location.

You probably have heard vintners say the clone number for a specific variety of grapes planted in their vineyard. An example of this would be the Pinot Noir Dijon clones 114, 115, 667, and 777 which are the most widely planted Pinot Noir clones because of their reliability and productivity. When you drink any mass-produced Pinot Noir you are likely drinking wine made from these clones. It is easy to go down a “rabbit hole” when looking for clones of just about any grape variety when researching which clones to plant in your vineyard. Don’t let the sheer number of options overwhelm you. The answer to this question is a simple one, treat a clone like a different variety. Pick a clone you like and propagate that clone.

Growing your own vines from cuttings is a rewarding venture both financially and from the sense of personal accomplishment you will feel when you harvest your first grapes. With the adverse effects of climate change being documented in vineyards around the world and the increased number of adverse weather events plaguing vintners, the answer to a consistent and economically sustainable fruit crop may lay in the past with heritage grape varieties, older cool climate hybrids, and new hybrids that are being developed. Growing heritage and cool climate hybrid grape vines that have adapted to survive many weather-related challenges over time could be a critical puzzle piece in the future viability of our vineyards, for both hobby and commercial grape growers. In addition, these varieties tend to be more productive and can be grown more sustainably with fewer pesticide/fungicide applications. They are direct producers that do not need to be planted on a rootstock. This means that if we witness a very cold winter or late spring frost, which kills that part of the vine above the ground, canes will come up from the ground to produce a crop in the same growing season.

With that objective in mind, Stephen Casscles continues to labor on his long-term project, the Cedar Cliff Vineyards Heritage Grape\Wine Project, aimed at preserving heritage and lesser-known cool climate grape varieties in Northern America. If you have any questions about his work at Cedar Cliff Vineyards please contact Stephen Casscles cassclesjs@yahoo.com To further his work, Stephen has established a set of three cooperating nurseries in Marlboro, NY, Fonda, NY, and Ipswich, MA where you can purchase already rooted vines and/or grape cuttings. If you are interested in obtaining cuttings of these unique vines, please feel free to contact Stephen Casscles cassclesjs@yahoo.com. Sadly, most of these cuttings or vines are not available at commercial nurseries, hence we need to propagate them on our own to increase the availability of these unique virus-free/ disease-free grape varieties. For additional information on these heritage and cool climate grape hybrids, the 2nd edition of Steve’s book “Grapes of the Hudson Valley and Other Cool Climate Regions of the US and Canada” is available at http://www.flintminepress.com .